contact:

diann@diannblakely.com

Visit us on Facebook

Site Copyright 2014

All Rights Reserved

020414

Part Four: Camille T. Dungy, Black Nature, The Goddess of Gumbo, Phillis Wheatley, and Ruin Nation

Hallelujah! Four more years of Obama, and who knows what poet Yusef Komunyakaa might see him reading next? Perhaps one of the many superlative but still “under-the-radar” poets of color not given the chance to speak—or read—for themselves at the Emory gatherings, both available on YouTube? But how to choose, I thought, head spinning, as I looked at my laden bookshelves? What about Camille T. Dungy, I thought, whom I’d first discovered through the “rogue sonnets” of What to Eat, What To Drink, What to Leave for Poison (Red Hen); then went on to read her ABA-winning Suck on the Marrow, as well as another anthology, From the Fishouse (Persea), co-edited with Matt O’Donnell and Jeffrey Thomson, with an introduction by Gerald Stern; and the truly ground-breaking—so to speak—Black Nature. Meanwhile, my admiration for Dungy’s work has only been increased by posts I’ve read at the Poetry Foundation, not to mention a new and previously unpublished poem, “Characteristics of Life,” and a recent essay in Waccamaw Review. In this same interim, however, Dungy began winning so many awards that I warned her to stop lest she fail to meet the classification of an “under-the-radar” poet. Did she listen? NO! Instead, she appears in this month’s issue of O!

Dungy’s newest collection, Smith Blue, was the most recent selected for the prestigious Crab Orchard Series in Poetry, while she herself was named as one of “ten poets to watch” by Rita Dove. In particular, I wondered, how did her editing of Black Nature inform this new book? Smith Blue begins with epigraphs by, respectively, Gwendolyn Brooks and C. D. Wright:

Dungy’s newest collection, Smith Blue, was the most recent selected for the prestigious Crab Orchard Series in Poetry, while she herself was named as one of “ten poets to watch” by Rita Dove. In particular, I wondered, how did her editing of Black Nature inform this new book? Smith Blue begins with epigraphs by, respectively, Gwendolyn Brooks and C. D. Wright:

Let us combine. There are no magic or elves

Or timely godmothers to guide us. We are lost, must

Wizard a track through our own screaming weed.

*

What elegy is, not loss but opposition.

DB: For those who haven’t yet met the “magic” of Smith Blue, which I would argue is, in fact, a “guide” for us, the lost ones screaming on Lear’s heath, could you offer some illumination as to how Brooks’s and Wright’s words bear on the poems in this new book?

CTD: This is a book of elegies, and also a book of praise. This is a guidebook for how to survive, even thrive, in the face of 21st-century local and global devastations. We are the ones who have to make a better world for ourselves and our loved ones and the strangers whose lives are connected inextricably to our own. No one else is going to do it for us. We can’t just sit down and mourn our losses. We have to actively work, to fight, to stop those losses from accumulating. How are we going to do this? We have to make our own traditions, build new tools, re-appropriate the language of loss and make it a language of hope. It will be, it is, hard work, but the results could be miraculous. And heaven knows, we need a miracle. Those are some of the things I think Brooks and Wright are saying in those particular passages, and those are some of the things I want the poems in Smith Blue to suggest.

DB: “After Opening the New York Times I Wonder How to Write a Poem About Love” is a poem of desolation, but as the book continues, you offer another titled “Out of the Darkness.” What is, precisely, the darkness and how do we escape?

CTD: The poem “Out of the Darkness” is, quite literally, a creation story, one which came from an attempt to write such a piece for/of my daughter. We all need our own creation myths, right? This is mine, hers. Hopefully, out of all the darkness that are these times, we can get some beauty, some brightness, something better. So many of the things I mention in that poem were things I saw right out my study window. The spider was on the back porch, the blackberry bramble in my backyard, but of course they are all remade in another light. I take what I see and see what I can make of it. That’s how we create story. That’s what a creation story is all about. But in the context of Smith Blue, especially the opening poem you mention, I am also trying to take the yuck I see and make something new, better, brighter for our world, not just for my poems. Though the tools I have to do that work are often poetry.

CTD: The poem “Out of the Darkness” is, quite literally, a creation story, one which came from an attempt to write such a piece for/of my daughter. We all need our own creation myths, right? This is mine, hers. Hopefully, out of all the darkness that are these times, we can get some beauty, some brightness, something better. So many of the things I mention in that poem were things I saw right out my study window. The spider was on the back porch, the blackberry bramble in my backyard, but of course they are all remade in another light. I take what I see and see what I can make of it. That’s how we create story. That’s what a creation story is all about. But in the context of Smith Blue, especially the opening poem you mention, I am also trying to take the yuck I see and make something new, better, brighter for our world, not just for my poems. Though the tools I have to do that work are often poetry.

I want to say, also, that I am not sure I agree that “After Opening the New York Times I Wonder How to Write a Poem About Love” is entirely a poem of desolation. You can read the last lines a few ways. “Turn the page./ Turn another page. This was meant to be/ about love. Now there is nothing left but this.” What is this? Desolation, perhaps. But maybe love. Maybe poetry. Maybe the world’s beauty. Maybe the turning of pages. Maybe it’s not so bad after all. Who knows. Turn the page and see.

DB: And how about music? Smith Blue ends with fireflies and bellies and boys and lifted bells—are we to understand that some sort of reconciliation has been reached with the world’s sorrows and at last, the right to make a joyful noise has been earned?

CTD: Sure. If that’s what you want to understand, go with it. The title of that poem is “Maybe Tuesday Will Be My Good News Day.” It’s a counterpoint to the first title, right? Of course, the closing title has the word “maybe” in it. So I’d suggest that I am being no more definitive in the end than I was in the beginning. Are you living in the same world I’m living in? There aren’t many definitive answers in it, and certainly not permanent ones.

CTD: Sure. If that’s what you want to understand, go with it. The title of that poem is “Maybe Tuesday Will Be My Good News Day.” It’s a counterpoint to the first title, right? Of course, the closing title has the word “maybe” in it. So I’d suggest that I am being no more definitive in the end than I was in the beginning. Are you living in the same world I’m living in? There aren’t many definitive answers in it, and certainly not permanent ones.

DB: In an essay called “Shore Lines,” you seem to be speaking, at least in part, to the way you’ve broken your earlier adherence to received forms in favor of the more . . . well, organic?

CTD: Am I? Hmm. I thought I was talking about the way that the ocean moves and how that reminds me of the ways a poem can move. I’ve never been a strict formalist, but I’ve always loved the revelation inherent in forms. So I don’t know that I am behaving any differently in Smith Blue than I was in Suck on the Marrow or What to Eat, What to Drink, What to Leave for Poison. My first book is a collection of rogue sonnets. They are all (usually) 14 lines. Every one has a volta at right around the normal place. They are syllabic, and often the syllable count is 10. But they are usually irregularly metrical if they are metrical at all. They are rhymed (or not rhymed) in their own many ways. Even while playing straight into a long-received form, I was playing fast and loose with it. So when, in Smith Blue, I write a 14-page acrostic and actually keep religiously true to the punctuation and capitalization of the original poem that runs through the first letter of each line, perhaps I am becoming more rigidly formal, not less. But that’s not it at all. I’m actually just going with the flow, doing what the poems tell me I need to do. That’s how I’ve always been, and that is likely how I will continue.

DB: Any ideas yet about the forms that continuance might take?

CTD: What I try to do as a poet is write a poem. Then I write another poem. Then I write another poem. Eventually I will begin to understand the form the poems are taking, but I don’t know that in any kind of global sense until I have a lot of poems in front of me. Part of the pleasure for me is discovering the answer to this question, and part of the pleasure is savoring the time when I don’t yet know the answer to that question. It is in that time when the joy of discovery that is writing is at its fullest potential.

DB: Robert Hass devotes an entire chapter to Black Nature in his own new book of selected prose, What Light Can Do: Essays on Art, Imagination, and the Natural World (Ecco). He closes by saying that “Camille Dungy has given all of us a gift.” In the wake of Superstorm Sandy, the nature, so to speak, of that gift has changed; though I’m taking these lines out of context, I find the clearest and most trenchant meaning in a poem by Gerald Barrax, Sr.: if we forget our history and ties to nature, he writes, “we are slaves again.” Isn’t that precisely what we—as Americans, African-American and white—have done in becoming masters of profit instead of the land’s stewards? Become “slaves again” to natural disasters like Sandy, which is being directly attributed to global warming?

DB: Robert Hass devotes an entire chapter to Black Nature in his own new book of selected prose, What Light Can Do: Essays on Art, Imagination, and the Natural World (Ecco). He closes by saying that “Camille Dungy has given all of us a gift.” In the wake of Superstorm Sandy, the nature, so to speak, of that gift has changed; though I’m taking these lines out of context, I find the clearest and most trenchant meaning in a poem by Gerald Barrax, Sr.: if we forget our history and ties to nature, he writes, “we are slaves again.” Isn’t that precisely what we—as Americans, African-American and white—have done in becoming masters of profit instead of the land’s stewards? Become “slaves again” to natural disasters like Sandy, which is being directly attributed to global warming?

CTD: One of the things that I think is most important to clarify, as both the anthology Black Nature and the essay Robert Hass wrote about African American nature poetry strive to clarify, is the fact that there is nothing new about these ideas you’re suggesting. Black people writing about the natural world is not some new phenomenon. Americans didn’t just start writing about the dangerous environmental repercussions of greed this summer. Human-exacerbated devastation is not a new phenomenon, and certain writers have been sounding the alarm all along. Things are getting worse, but even that shouldn’t be coming as a surprise. Poetry is not new. Storms are not new. Poems about storms are not new. Barrax, Lucille Clifton, Sterling Brown, so many of the poets in Black Nature, show us that thinking about the nonhuman world is necessary for survival. I write in this way, Robert Hass writes in this way, but we are not alone or original in writing in this way. How we say what needs to be said might be uniquely crafted, but the message is as old and necessary as soil. And as easy to squander.

CTD: One of the things that I think is most important to clarify, as both the anthology Black Nature and the essay Robert Hass wrote about African American nature poetry strive to clarify, is the fact that there is nothing new about these ideas you’re suggesting. Black people writing about the natural world is not some new phenomenon. Americans didn’t just start writing about the dangerous environmental repercussions of greed this summer. Human-exacerbated devastation is not a new phenomenon, and certain writers have been sounding the alarm all along. Things are getting worse, but even that shouldn’t be coming as a surprise. Poetry is not new. Storms are not new. Poems about storms are not new. Barrax, Lucille Clifton, Sterling Brown, so many of the poets in Black Nature, show us that thinking about the nonhuman world is necessary for survival. I write in this way, Robert Hass writes in this way, but we are not alone or original in writing in this way. How we say what needs to be said might be uniquely crafted, but the message is as old and necessary as soil. And as easy to squander.

DB: As easy as it is to offer my assent to your every point.

*****************************************

And how about Kendra Hamilton, a/k/a The Goddess of Gumbo, the title of her début poetic collection (WordTech Press), a self-described “generalist” who, in addition to serving as Charlottesville’s vice mayor, counts environmental issues and sustainable farming among her passionate interests?  Furthermore, her career as essayist and expertise on regional and ethnic cuisine—pure Geechee-Gullah, she talks to her ancestors on a daily basis—plus a background in health journalism and historical ecology make her perfect to explore how these concerns intermix, so to speak, in Ruin Nation, Megan Kate Nelson’s study. Neither of us knew, for example, about a stereograph called Wounded Trees, which describes “arboreal carnage” sustained during the Civil War, when “soldiers hit more trees than men during any given engagement” or that their “rifles and artillery, long-range and increasingly accurate, took a significant toll on southern forests, especially those along rivers and in Virginia,” where Hamilton now teaches and “the largest Union and Confederate armies clashed.”

Furthermore, her career as essayist and expertise on regional and ethnic cuisine—pure Geechee-Gullah, she talks to her ancestors on a daily basis—plus a background in health journalism and historical ecology make her perfect to explore how these concerns intermix, so to speak, in Ruin Nation, Megan Kate Nelson’s study. Neither of us knew, for example, about a stereograph called Wounded Trees, which describes “arboreal carnage” sustained during the Civil War, when “soldiers hit more trees than men during any given engagement” or that their “rifles and artillery, long-range and increasingly accurate, took a significant toll on southern forests, especially those along rivers and in Virginia,” where Hamilton now teaches and “the largest Union and Confederate armies clashed.”

The results in terms of suffering—ecological, financial, and health—stretch past the War’s sesquicentennial. In fact, they have proved catastrophic in terms of agribusiness, our estrangement from the land which should sustain us, and the related, sky-rocketing rates of heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and obesity that comes from eating pre-fab food; and yes, race is also a factor. (Relatedly, see Alice Randall.)

I’d discovered Hamilton’s poetry relatively long ago, in The Ringing Ear: Black Poets Lean South, edited by 2011 NBA winner Nikky Finney and published jointly by UGA Press and Cave Canem. Other than updating the latest titles by the six poets I singled out in 2007, this archived review remains untouched. I immediately ordered Hamilton’s savory title—in fact, she gave me my closing line—but no sooner had my proposal to write about The Goddess of Gumbo à seul been accepted than the venue dropped all its literary coverage as though it were a skillet popping with hot grease. Frustrated, at least I had confirmation via another early piece in good downhome prose with a dark roux, describing The Goddess of Gumbo as exploring “issues of race, love, memory and failed expectation” with “more than memory and lyric language,” and the poet as “a master of sweet words, fine metaphor and evocative simile, yet when you consider what she’s writing about, her work has a bite.”

I’d discovered Hamilton’s poetry relatively long ago, in The Ringing Ear: Black Poets Lean South, edited by 2011 NBA winner Nikky Finney and published jointly by UGA Press and Cave Canem. Other than updating the latest titles by the six poets I singled out in 2007, this archived review remains untouched. I immediately ordered Hamilton’s savory title—in fact, she gave me my closing line—but no sooner had my proposal to write about The Goddess of Gumbo à seul been accepted than the venue dropped all its literary coverage as though it were a skillet popping with hot grease. Frustrated, at least I had confirmation via another early piece in good downhome prose with a dark roux, describing The Goddess of Gumbo as exploring “issues of race, love, memory and failed expectation” with “more than memory and lyric language,” and the poet as “a master of sweet words, fine metaphor and evocative simile, yet when you consider what she’s writing about, her work has a bite.”

Then Hamilton sprang up again, this time—guess where?—with Black Nature itself; the poem appearing here turns diamond-sharp, with its double entendre of “Southern Living.” Her newest projects themselves are dual, reflecting prismatically additional-yet-related and “natural” obsessions:

I’m on the final chapter of a work of serious scholarship: The Geography of Desire: Romancing Blackness on the Gullah/Geechee Coast. I’m also working more and more seriously on new poems. The working title is Mirrours of the World—it’s a narrative sequence about sex (in the gender sense), lies, and shopping among the Robber Barons.

I’m on the final chapter of a work of serious scholarship: The Geography of Desire: Romancing Blackness on the Gullah/Geechee Coast. I’m also working more and more seriously on new poems. The working title is Mirrours of the World—it’s a narrative sequence about sex (in the gender sense), lies, and shopping among the Robber Barons.

My subject is Belle Da Costa Greene, J.P. Morgan’s librarian, the first director of the Morgan Library, and a world-renowned expert on illuminated manuscripts and incunabula. She was a woman who succeeded as few others have in the man’s world of rare books and manuscripts. She was also a black woman passing for white.

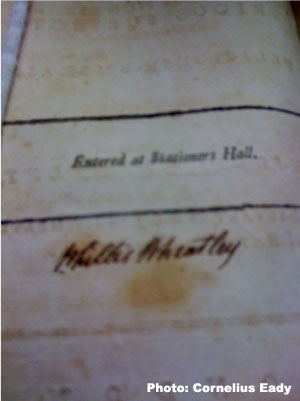

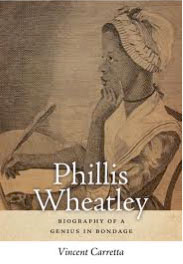

Phillis Wheatley was “passing” too, though not in the way the word usually connotes. She cultivated a “canny”—to use the word Oline Wheaton, a reviewer, deploys—image no less carefully than Morgan concocted a fortress of taste behind which Belle could hide. But considering both women’s choices, weren’t they victims as well, not just two pairs of  shrewd eyes on the main chance? In Wheatley’s case, is it fair to imply that she was hungry for fame and expert in what we now call “self-marketing”? “Even her evangelical Christianity,” Wheaton continues, “was a subtle rebellion against slavery and also the means by which she got her words into print. The Wheatley who emerges in Biography of a Genius in Bondage is an alarmingly modern character . . . innovative and determined to get her poems into print. That she was able to do so as a woman in the 18th century is impressive. That she was able to do so as a slave is extraordinary.” And from Publishers Weekly: “This is a satisfying study of the ‘elusive’ Wheatley, fleshed out with succinct, discerning readings of the body of her work. . . . Especially noteworthy is the book’s attentiveness to Wheatley’s involvement in the production and promotion of her book.”

shrewd eyes on the main chance? In Wheatley’s case, is it fair to imply that she was hungry for fame and expert in what we now call “self-marketing”? “Even her evangelical Christianity,” Wheaton continues, “was a subtle rebellion against slavery and also the means by which she got her words into print. The Wheatley who emerges in Biography of a Genius in Bondage is an alarmingly modern character . . . innovative and determined to get her poems into print. That she was able to do so as a woman in the 18th century is impressive. That she was able to do so as a slave is extraordinary.” And from Publishers Weekly: “This is a satisfying study of the ‘elusive’ Wheatley, fleshed out with succinct, discerning readings of the body of her work. . . . Especially noteworthy is the book’s attentiveness to Wheatley’s involvement in the production and promotion of her book.”

Since Hamilton also had the recent distinction of being the keynote speaker at the 95th anniversary celebration of the Phillis Wheatley Literary Society and Social Club, founded in 1916 in her hometown of Charleston, I thought she’d be amply prepared to offer a take on the Wheatley bio, yet another title from UGA Press.

Phillis Wheatley, yes, she was a genius of manipulating language. That’s one of the real contributions made by Vincent Carretta’s new biography. He does a great job of establishing Wheatley’s place in the context of her peers and contemporaries versus the context of what T.S. Eliot would have recognized as the poetic “tradition,” thus demonstrating the central fallacy in that famous dismissal of her talent by Thomas Jefferson. Carretta, though, doesn’t compare Wheatley to Pope—he compares her more appropriately to people like Philip Freneau, who enjoyed Jefferson’s patronage, and poets in the New England religious verse tradition. None of these poets, he demonstrates, were the equal of the Augustans, while being influenced to a greater or lesser extent by them—and of this group, Carretta demonstrates Wheatley’s superiority to her peers.

It’s an important nuance for Carretta to demonstrate the degree to which Phillip actively negotiated with the Wheatleys to arrange her own emancipation before she departed for England to promote her book. Was that manipulation? Absolutely. But what Phillis never is able to become is the mistress or even the successful manipulator of her own circumstances. And that’s, in my opinion, the ironic consequence of the education that makes her such a social outlier in terms of race and gender. In that respect she reminds me of another woman educated far beyond her station in life and her gender: Jefferson’s daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, who received a convent education during her father’s ambassadorship that would have equipped her to join one of the most highly refined, educated, and brilliant courts in Europe, only to find herself mired in Virginia for the rest of her life with only her father’s friends to talk to.

Patsy Jefferson, at least, had the protection of this brilliant company, the protections of her unassailable class position. Phillis Wheatley had only the Wheatleys. And once freed, she had not even the backhanded celebrity status offered by her enslavement. There was no circle of peers to support her intellectual pursuits—no clear path, as a woman of African descent lacking patronage, to profit by her intellect, particularly in the environment of severe economic depression in the wake of the Revolutionary War. Her husband jailed as a debtor, her health failing, we are left to imagine those final days living in squalor with a dying child in which her despair must have been complete.

Patsy Jefferson, at least, had the protection of this brilliant company, the protections of her unassailable class position. Phillis Wheatley had only the Wheatleys. And once freed, she had not even the backhanded celebrity status offered by her enslavement. There was no circle of peers to support her intellectual pursuits—no clear path, as a woman of African descent lacking patronage, to profit by her intellect, particularly in the environment of severe economic depression in the wake of the Revolutionary War. Her husband jailed as a debtor, her health failing, we are left to imagine those final days living in squalor with a dying child in which her despair must have been complete.

So no, I don’t think of Phillis Wheatley Peters as a master manipulator—I see a fate shared by far too many who aspire to a writing life. Commitment, sustained creation, undercut by circumstances. And among the shards of her shattered existence, beautiful poems gleaming with a cold beauty that cannot be denied or silenced. In a different world, her early acclaim might have lead to something that could have sustained a long career and continued artistic production. And perhaps that different world was simply England, where she could have joined the circle around Ignatius Sancho and Granville Sharpe. But in America, ironically, tragically, “land of the free,” the promise proved a lie.

Did I mention that another of Hamilton’s specialties is gender history?

090313 11:00