contact:

diann@diannblakely.com

Visit us on Facebook

Site Copyright 2014

All Rights Reserved

020414

Controversies, Connections, and Coincidences

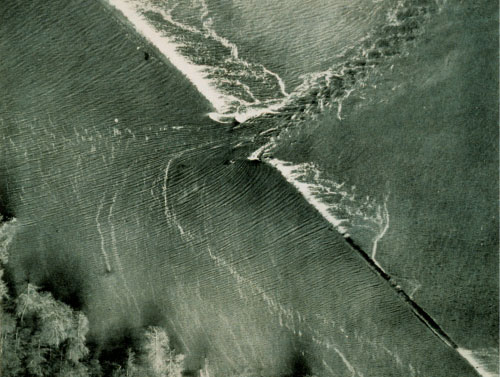

“...the music crept by me on the waters...”

T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land

“My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

Langston Hughes, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”

Part One: Take Me, Wash Me, Cleanse Me, Etc.

By now, readers of this series have been made aware to an extreme, and perhaps obnoxious, degree of the weight I give to coincidences, superstitions, and that strange magic called juju, for good and bad. Katrina made landfall on 29 August 2005. Five years later, just before a weekend of commemorative events—poetic, musical, dramatic, and otherwise—took place, following the première of Spike  Lee’s If God is Willing and Da Creek Don’t Rise, I wrote a duo of preview pieces, “Interim” and “When the Saints Went Marching Out.” Starring was Lee’s 2010 film, which Alison Pelegrin—winner of this year’s 11th Annual Erskine J. Poetry Prize from Smartish Pace for “Pantoum of the Endless Hurricane Debris”—promptly proclaimed had her on her knees again, referring to When the Levees Broke: A Requiem, his first post-Katrina documentary.

Lee’s If God is Willing and Da Creek Don’t Rise, I wrote a duo of preview pieces, “Interim” and “When the Saints Went Marching Out.” Starring was Lee’s 2010 film, which Alison Pelegrin—winner of this year’s 11th Annual Erskine J. Poetry Prize from Smartish Pace for “Pantoum of the Endless Hurricane Debris”—promptly proclaimed had her on her knees again, referring to When the Levees Broke: A Requiem, his first post-Katrina documentary.

My own efforts’ successor, which was to have been published on 29 September 2010, bore the title you now see above, but without the second two words. I am adopting this date—meaning the 29th—for future posting of all remaining items in the “SoPo” series, as I have come to call it. For it seems proleptic.

Indeed, to toss even more ingredients into the metaphorical pot of gumbo represented by this column, on the same date, a notice arrived from the Poetry Society of America, which, with Tulane, had co-hosted an event in New Orleans during the Katrina commemorative weekend. (You will see the word “gumbo” several times here, but could there be more a applicable term in the national lexicon?) The forewarned (?) Atlanta panels/readings took place on October 7th in conjunction with Emory. Ted Hughes, whose papers are deposited there, would have loved all of this, being an expert on horoscopes, folklore, the Ouija board, and, some say, haruspicy. He even believed that his death was caused by writing too much prose, and I fear I am headed for the same fate.

Some of you attended. I wrote immediately that I welcomed reports back, or from the front, I should say, for immediate grumblings were heard, just as before and after the Tulane reading six weeks before. You can go to the site for particulars, but I’ll list the participants’ names for the Atlanta events: “The Future of Southern Poetry” included Beth Bachman, Sean Hill, Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, and Jake Adam York, with Kevin Young; and “Poets of the American South, 1910-2010” with Claudia Emerson, Terrance Hayes, Forrest Gander, Thomas Lux, Natasha Trethewey (who, in just a few days, will assume her duties as our country’s Poet Laureate—the first from the South since Robert Penn Warren), C. D. Wright. and Young again. Wright—whose most recent collection, One With Others (Copper Canyon Press), along with native South Carolinian Hayes’s Lighthead (Penguin)—had just been nominated for the National Book Award. Both the discussion and the reading were described as a celebration “of the great tradition of Southern Poetry in America over the past century.” The initial panel consisted of ten-minute slots in which the participants were asked to read from the work of a Southern poet they deemed canonical, and the second of a discussion of the roots of that tradition and how it might continue.

Some of you attended. I wrote immediately that I welcomed reports back, or from the front, I should say, for immediate grumblings were heard, just as before and after the Tulane reading six weeks before. You can go to the site for particulars, but I’ll list the participants’ names for the Atlanta events: “The Future of Southern Poetry” included Beth Bachman, Sean Hill, Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, and Jake Adam York, with Kevin Young; and “Poets of the American South, 1910-2010” with Claudia Emerson, Terrance Hayes, Forrest Gander, Thomas Lux, Natasha Trethewey (who, in just a few days, will assume her duties as our country’s Poet Laureate—the first from the South since Robert Penn Warren), C. D. Wright. and Young again. Wright—whose most recent collection, One With Others (Copper Canyon Press), along with native South Carolinian Hayes’s Lighthead (Penguin)—had just been nominated for the National Book Award. Both the discussion and the reading were described as a celebration “of the great tradition of Southern Poetry in America over the past century.” The initial panel consisted of ten-minute slots in which the participants were asked to read from the work of a Southern poet they deemed canonical, and the second of a discussion of the roots of that tradition and how it might continue.

My first questions might well be yours: why were these particular panelists chosen, and what is the ultimate meaning of their selection, as opposed to that of others who might have been included? Second, if New Orleans and Atlanta are the epicenters of Southern poetry, what does that say for the rest of cities and small towns, not to mention the “country,” where most Southerners derive their origins, if only by a generation or two? Last, what is a “Southern poet,” and is this further ghettoization of writers who would otherwise shine unassisted by geography, or a good way of understanding who they are and the contexts in which they write?

Am I the best one to answer such questions? Hell, no! For as I’ve already admitted on the Facebook page I created as a supplement for the series itself, I was not at all equipped for this task: I am, yes, from the South, but in addition to an ongoing, intermittent battle with a Quentin Compson Complex, I spent many years in New York City, 02138, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Nashville. The last locale, which to me always seemed like the Lower Midwest, is home to Vanderbilt University, endowed by the Commodore’s robber baron billions through a chance finger placed on a map. “Might as well be in Brooklyn,” a friend quipped of the school, which here has significance only because the PSA co-sponsored its third Centennial Year event there, and the poet selected was Northern Ireland’s Ciaran Carson, which caused no grumblings at all.

Am I the best one to answer such questions? Hell, no! For as I’ve already admitted on the Facebook page I created as a supplement for the series itself, I was not at all equipped for this task: I am, yes, from the South, but in addition to an ongoing, intermittent battle with a Quentin Compson Complex, I spent many years in New York City, 02138, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Nashville. The last locale, which to me always seemed like the Lower Midwest, is home to Vanderbilt University, endowed by the Commodore’s robber baron billions through a chance finger placed on a map. “Might as well be in Brooklyn,” a friend quipped of the school, which here has significance only because the PSA co-sponsored its third Centennial Year event there, and the poet selected was Northern Ireland’s Ciaran Carson, which caused no grumblings at all.

In addition to my moves and QCC, however, a further handicap to the series was that earlier confession about tending to lack interest in any poetry I don’t find dulce et utile: I read for delight, for education, to revel in language, and to inform my work, whose obsessions have changed from book to book; in the past two years, I have set poems in Texas, Akhmatova’s Russia, Mississippi, London, Alabama, Yorkshire, New Orleans, Virginia, Los Angeles, and Nashville, believing the deep truth of a statement by Richard Tillinghast (see Jennifer Horne’s review of his recent Selected Poems): it’s not that Southern writers are born with a sense of “one dear perpetual place,” but for some of us “the world is a place,” and attunement to its locales is a variety of what Keats called “negative capability,” as he wrote first in Threepenny Review, then in his most recent collection of essays, Poetry and What Is Real. If wholly uninformed about the many cultures within the South, except intuitively—“these people speak with the most peculiar accent,” said my mother, in her Virginia cum Black Belt drawl on a visit to Nashville, illustrating her own aural "attunement"—and the different poetries that sprang, and continue to spring, therefrom, perhaps this hasn’t proved to my disadvantage.

In addition to my moves and QCC, however, a further handicap to the series was that earlier confession about tending to lack interest in any poetry I don’t find dulce et utile: I read for delight, for education, to revel in language, and to inform my work, whose obsessions have changed from book to book; in the past two years, I have set poems in Texas, Akhmatova’s Russia, Mississippi, London, Alabama, Yorkshire, New Orleans, Virginia, Los Angeles, and Nashville, believing the deep truth of a statement by Richard Tillinghast (see Jennifer Horne’s review of his recent Selected Poems): it’s not that Southern writers are born with a sense of “one dear perpetual place,” but for some of us “the world is a place,” and attunement to its locales is a variety of what Keats called “negative capability,” as he wrote first in Threepenny Review, then in his most recent collection of essays, Poetry and What Is Real. If wholly uninformed about the many cultures within the South, except intuitively—“these people speak with the most peculiar accent,” said my mother, in her Virginia cum Black Belt drawl on a visit to Nashville, illustrating her own aural "attunement"—and the different poetries that sprang, and continue to spring, therefrom, perhaps this hasn’t proved to my disadvantage.

Or, to quote the late Eleanor Ross Taylor on the subject, despite her “fierce attachment” to the part of North Carolina in which she was reared, “I don’t think of myself as a Southern writer.” I’ll add only a rejoinder to read Betty Adcock on the subject, which made me envision, for the first time, the phrase “White Southern Female Poet” personally applied, and in print. The horror I felt when envisioning doilies and sterling silver iced tea spoons was followed by a small, humiliating weeping fit, then a determination that I would somehow prove myself worthy of two, and only two, such modifiers attached to the word “poet” in relation to me: “damn” and “fine.”

For what else might I strive, spurning labels of any sort and having moved twenty-four times in fifty-odd years, thirty-five of those spent at three addresses? Part, yes, Southern but part déraciné unto eternity, I remain semi-itinerant, my soul’s suitcase packed with the lessons garnered from a long line of stellar teachers, only one of which, Donald Justice, hails from my native region—indeed, among the few Americans!—though his work explodes past any such definition; when we met, he’d been living in Iowa City for so long that I noticed no trace of an accent, just a dissatisfaction with temperatures below seventy degrees. I can still see him slumped against the chill Vermont rain at Bread Loaf, anorak hood pulled over his forehead; once, when I heard a strange squishing noise, I discovered his only pair of shoes was soaked. Mrs. Taylor and her brother-in-law, both master poets, knew little of my generation’s tricky devices: I led Justice to my room and, wielding a blow-dryer, inserted the nose into the leather while keeping the shoes wrapped in a towel. Such gratitude has rarely been witnessed, and quieter murmurs of appreciation for my early poems inspire me still to rapture.

For what else might I strive, spurning labels of any sort and having moved twenty-four times in fifty-odd years, thirty-five of those spent at three addresses? Part, yes, Southern but part déraciné unto eternity, I remain semi-itinerant, my soul’s suitcase packed with the lessons garnered from a long line of stellar teachers, only one of which, Donald Justice, hails from my native region—indeed, among the few Americans!—though his work explodes past any such definition; when we met, he’d been living in Iowa City for so long that I noticed no trace of an accent, just a dissatisfaction with temperatures below seventy degrees. I can still see him slumped against the chill Vermont rain at Bread Loaf, anorak hood pulled over his forehead; once, when I heard a strange squishing noise, I discovered his only pair of shoes was soaked. Mrs. Taylor and her brother-in-law, both master poets, knew little of my generation’s tricky devices: I led Justice to my room and, wielding a blow-dryer, inserted the nose into the leather while keeping the shoes wrapped in a towel. Such gratitude has rarely been witnessed, and quieter murmurs of appreciation for my early poems inspire me still to rapture.

I’ve never ceased taking instruction also from mentors-on-the-page, early and late: all shared an emphasis on arranging a page’s scribbles to make an aural effect. I’ve mentioned many of these in the series, and you’ll find an even larger number here, but it bears repeating that these include the epigraphs’ authors; Shakespeare, whom Keats read instead of despairing; the King James Bible; and, again, the blues (Justice, like Kim Addonizio and Baron Wormser, has written some superb poems in this form), singing wherever the four winds have blown me. And if I have a primal loyalty to the South, it’s to the language I absorbed into my body as a child: again, the KJB and the Elizabethan / Jacobean diction and cadences of the Book of Common Prayer.

Last, just when I thought I’d finished this essay, I came across Hilton Als’s review of the first multi-racial production of A Streetcar Named Desire. Anyone who knows me is aware of my reverence for Tennessee Williams, whom I have called—so many times that I’m afraid I’m quoting myself—the South’s Shakespeare, not that he was of that level—for who is?—but that he strove to elevate the Southern vernacular to the level of poetry. “Toward the end of the play,” Als writes, “when it’s clear that Mitch won’t save Blanche by marrying her, she offers him a drink. Peering at the label on the bottle, she says, ‘Southern comfort. What is that, I wonder?’ With that line, Williams makes a wry comment not only about Blanche’s place in the South but about his own contribution to Southern literature. He was no professional Southerner, but by the time Streetcar was made into a film in 1951, critics were marginalizing him as such. In the movie, Vivien Leigh utters the line derisively; she’s in on Williams’s bitter camp meaning. In Stanley and Stella’s world, her Southern graciousness is a joke—and no comfort.”

Last, just when I thought I’d finished this essay, I came across Hilton Als’s review of the first multi-racial production of A Streetcar Named Desire. Anyone who knows me is aware of my reverence for Tennessee Williams, whom I have called—so many times that I’m afraid I’m quoting myself—the South’s Shakespeare, not that he was of that level—for who is?—but that he strove to elevate the Southern vernacular to the level of poetry. “Toward the end of the play,” Als writes, “when it’s clear that Mitch won’t save Blanche by marrying her, she offers him a drink. Peering at the label on the bottle, she says, ‘Southern comfort. What is that, I wonder?’ With that line, Williams makes a wry comment not only about Blanche’s place in the South but about his own contribution to Southern literature. He was no professional Southerner, but by the time Streetcar was made into a film in 1951, critics were marginalizing him as such. In the movie, Vivien Leigh utters the line derisively; she’s in on Williams’s bitter camp meaning. In Stanley and Stella’s world, her Southern graciousness is a joke—and no comfort.”

Penultimately, I must request some homework from readers: in order for this essay to approach any kind of sense, a familiarity with those originating “controversies” is required and can easily be located by following the embedded links: Tulane; then Emory, here and here. A thorough and thoughtful familiarity of both events is our starting place: I’ve had a couple of years to ponder the reactions and questions provoked, which led me to others. Since these may not reflect your own, please consider forming some as “Homework, Part Two.”

On the other hand, I don’t want this essay to rest solely upon “controversies,” with others or with myself, so perhaps it’s best to begin aided by Als and two other poets far better qualified than I to answer certain questions about Southern-ness, language, variant cultures, religion, and the rich gumbo they comprise in New Orleans perhaps better than anywhere else in the country. So how about Mona Lisa Saloy, whose first book, Red Beans and Ricely Yours, won the T. S. Eliot Prize and arrived at my door bearing jacket recommendations by Ishmael Reed and Dave Smith? The appendix “A Creole Dictionary” is nearly as delicious as the book’s contents. While no “formalist,” strictly speaking, Saloy (our first coincidence! her name rhymes with . . .) takes obvious “joy” in the words she chooses for each page. And also Jennifer Reeser, most recently author of Sonnets from the Dark Lady and Other Poems (St. James Infirmary Press), which includes “Proper Creole Farewells,” and was reviewed with insight, stringency, and “proper” admiration by Kim Bridgford in Mezzo Del Cammin. Further illumination can be found in the following interview with Reeser. Perhaps you’ll be willing to consider reading both books—ordered from the “small” / university presses that published them, please! though I know I’m repeating myself—in addition to watching the YouTube items above. After all, you have an entire month!

092012 1634